JOSIP NOVAKOVICH

JOSIP NOVAKOVICH

RUBBLE OF RUBLES

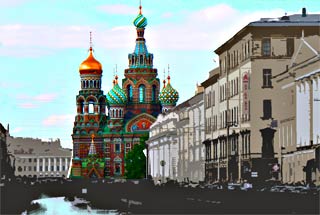

excerpt from Drawbridges of Saint Petersburg

At the corner of Canal Griboyedova and Lomonosova, David entered a diesel cloud in which lay a human body limply in front of an olive-green truck full of smoking black asphalt. A driver and another man in dusty blue worker’s clothes looked at the prostrated body and smoked; they passed a cigarette back and forth like a joint. The laborer poked the body with his cement-dusted shoe. Then the two men climbed into the truck and backed away from the body into a Volkswagen Golf, crushing the left headlight and crunching the hood, and drove away down Lomonosova and wherever their sticky asphalt was wanted.

Armenian shop assistants from a 24 Chasa store stood on the opposite corner. A huge Georgian cook with thick eyebrows came out in his white-cap from the Avla-Bar. After him came a waitress in high-heels, her hair streaked blond on black, her lips glaringly scarlet. David wondered whether it was some boutique lipstick, such as Obsession (was there such lipstick?), or whether it was a lead-enriched Russian lipstick. Lead for some reason enhanced color, and Hungarian paprika gained its startling redness from it. It seemed strange, and yet perhaps not so strange, that lips would carry the element of bullet on them to appear more seductive, bloody. She gingerly walked over to the body, and yelled at the people, Why don’t you help him?

She flipped the body over on its back, dragged it closer to the railing of the canal and away from the potential traffic, against the high pink-stone sidewalk. Then she kneeled, her crotch over his crotch, and she pumped his chest with her palms, then slid up his torso and blew her breath into his mouth. David couldn’t avoid noticing in this emotionally taxing and alarming moment that her mini-skirt wasn’t quite buttoned on the side to the top, and her red thong led into her crack precipitously. He wondered whether she was Russian or Georgian.

He contemplated the possibility that his life would pass, and he would have never slept with a Russian, or for that matter a Georgian. There were many other more meaningful and painful omissions (such as that he hadn’t developed a strong perfectly healthy body or bought real estate in Istria), but this one struck him as the most immediately deplorable. Yet another life without Russian sex. From the bacteriological aspect, that was a blessing, but from the cardiovascular, it could be a punishable transgression, or rather, lack of transgression; the sheer regret could damage his heart-muscle, maybe make it big and saggy. If it grew big and saggy, it would miss many beats, and he’d get to be one of those panting fatsos who break into sweat as soon as they take five steps up a staircase.

He snapped out of his regretful thoughts as things could always get worse, as they did for the young man. Despite looking slutty, the waitress was clearly a fine and generous person, a real mensch. You can never draw conclusions from appearances. You would imagine that an authentic looking Georgian cook with a barrel-sized belly would be more likely to be big-hearted, but he only flipped the butt of his cigarette with his thumb before struggling back into the bar; the butt arched across the street onto a parked black Lada.

She pumped the athletic body for about three minutes and stood up in exasperation, cleaned the dust off her knees with her palms, then shouted more at the people for not helping right away and walked back to the restaurant, buttoning the top of her green skirt. Now, if this hadn’t revived the healthy looking corpse, nothing would—that must have been the general conclusion. Everybody walked away. Nobody wept. The traffic continued as normal, and the young man lay in the street, face up, his lips scarlet with her lipstick. As he lay outside the gay club, Greshniki (sinners), with black doors and signs marked in red, he would probably seem to be a victim of hate-crime.

What is the 911 number in this country? thought David. Maybe I should call? Oh, I am sure someone called. Every country has its own way of dealing with the dead, and Russians have had enough practice, so they should know what to do. And I don’t have a cell phone, unlike everybody else. One more reason to get one—safety.

David walked into a used cell-phone store at the Gostiny Dvor subway station and bought an old-style Nokia, heavy and thick as a little brick. The shop assistant used his own document, passport, to register the new SIM card and to assign him the number.

Just don’t buy drugs using the phone, or don’t kill anybody, and if you do, don’t talk on the phone about it, or they might look for me, said the assistant.

On the way, he had a couple of blini with red caviar at Coffee Break. The caviar was called red but was orange; the oval translucent eggs burst infusing salt into his tongue. He wondered whether he savored the eggs or salt; he had been on a low-salt diet to control his blood pressure. The eggs looked like albino eyes spooned out of little creatures, and perhaps these were eyes sold as eggs. Each egg was a potential creature, a soul waiting for incarnation; maybe each egg was an eye, seeing into the future of life, its life and other lives. He shivered as you usually do when something is tasty and slimy, appealing and repulsive, and this state between desire and disgust energized him, shaking him up. Caviar: it is life, was life, would be life. To cut that slimy feeling, he ordered a shot of vodka.

David walked out of the café and past a billiards bar, which inevitably looked like the Van Gogh painting with all the green and the reddish caviar-eyed, drunken players.

Along the canal fence, a blonde long-nosed woman in a black fur coat and a short gray wool skirt and classic black stockings was leaning over the corpse of the young man, holding his head in her left arm, and kissing him, angling her face sideways so their noses wouldn’t collide. Then she set him down gently, but his head still produced a thud on the pink granite, and another woman who was weeping without text kneeled, kicking off her blue stilettos and kissed him in the same manner, while seagulls flew above and shrieked, as though they were vultures caught in beautiful pristine bodies of sailing birds. The second woman dropped the young man’s head a little less cautiously, and it thudded the same, no louder than the first time, on the marvelously thick granite.

Who were these women? Lovers? Sisters? With Russians, who kiss on the lips unpredictably, it’s hard to tell. Probably lovers, getting ready to go to a club to grieve for the lost love on the dance floor. Or maybe they were strangers touched by the poetry of death in the streets. So the abandoned young man was developing a good social life, perhaps a better one than he’d had while alive, just when it looked as though nobody cared for him. Nevertheless, when you are this beloved, how can you remain lying dead in the street for hours? Will it become a fashion now for expensively dressed ladies to stop by and kiss the fit corpse? The corpse did look almost good, like a New Russian, a rejuvenated Anatoly Karpov with boney and intelligent-looking features, but buffed up, fed, not so high-strung (obviously, low-strung), and olive-skinned rather than the Nordic salmon-herring cross of color. His prosperous looks and former status seemed almost enviable, and that was perhaps the cause of his death. But was he dead? He looked too good for someone dead. Maybe this was all being filmed out of a parked car, a reality TV show for the city audience to laugh at the ridiculous callousness of current Russia, or maybe it was a movie-set. In that case, the actor was a good one, staying limp so long, reacting to nothing, not even to concussions.

Ahead of David sprawled a long courtyard park and sounds of invisible people drinking and laughing. He put the magnetic key against the house door, leading to the building where he stayed, and it clicked open. Orange light coming from the floor above helped him to make out the hallway and the stairway without waiting long for his eyes to adjust. On the staircase the black cat stood in the same spot, on the second stair, and stared at him with the same transcendental caution, his eyes fluorescing, as though he was responding to a different dimension, something that was invisible to David but visible to him, an ultraviolet cosmos. If one could look deep into Russia with ultraviolet rays, what would one see?—other than huge mineral deposits and various well-preserved mammoths.

The elevator brought him up to the fifth floor with much violent clanking. He opened the double door of the elevator, resembling a saloon door, and then shut the door leading to the corridor. Walls were being torn down for reconstruction, and the cement particles floated and immediately began to clog his nostrils, cementing them. It seemed all this reconstruction business was a mummification process, turning everyone into a mineral deposit.

He entered the apartment and walked across the floor, which shifted and the cupboards opened from the shaking of the flimsy floorboards and cemented reeds. Maybe it was one of those floors Viktor Shklovsky wrote about in A Sentimental Journey: during the winter of 1921, when people ran out of coal and wood to burn in their stoves, they burned books, and when they ran out of Pushkin and Dostoyevsky, they burned the floorboards stripping whole sections of their apartment floors. In some cases a whole family with the remaining furniture would fall through to the floor below. This apartment seemed to have undergone such a treatment, and the linoleum floor and a few reeds and a bit of mortar and cement were slapped over to cover up some of the holes; nevertheless, a well-fed American or Russian might in a misstep visit the neighbors below.

He collected the garbage in the apartment to dump on the way (he had a purging and cleansing impulse after the evening)—spent matches, old socks, which he wouldn’t wash, a bottle of curdled milk, several empty blue cans of Baltika, old folded g-mail papers, online reservations printed out, and three empty green bottles of Borjami, the Georgian mineral water. There were apparently no glass recycling containers in Russia; in a country so rich in natural resources and so polluted, recycling seemed to be pointless; the stores did however buy back empty bottles, and actually, drunks who hung out in the yards were a recycling army; they combed garbage for the bottles, to drink the dregs and to collect a few rubles. This time the black cat followed him into the night when he opened the metal door. Are we making friends? He leaned to pet the creature of intuition, but the cat sprang away from him.

As he walked away, the tomcat hissed, but followed him, perhaps enticed by the smell of curdled milk. Through a gate in the cage-like iron fence, David watched the Swedish section, the most elegant, mostly frescoed section of the city. The lights of the James Cook bar beckoned into sophisticated safety, yet that seemed far away, viewed from the dark yard with the rusty containers of garbage, like another country beyond the Iron Curtain.

He swung the bag of his garbage into the closest container, and the bag produced a shushed sound as it landed rather than the usual bang of bottles against the metal; something soft absorbed the sound. He peered over the edge of the container; there was a human body. Perhaps a discarded mannequin from one of the fashion stores lining up Nevsky? Or a drunk? Or the corpse from Griboyedova? How would he find out? Well, a drunk would be basically normal temperature, and at worst a couple of degrees cooler than a sober man. A corpse dead for twelve hours would manage to be chillier than that, and even chillier than plastic. He touched the man’s hand. Amazingly cold and elastic—certainly not gypsum. What kind of body laboratory is that, that kicks into motion and makes a body colder than regular objects, such as discarded plastic bottles filled with curdled milk? Maybe it’s somebody else’s corpse. Maybe there is no shortage of corpses. Well, he’d find out if he could feel the lipstick on the corpse’s lips, from the Georgian waitress’s failed resuscitation attempt and from the series of lovers. He was reluctant, sniffing in the smells of rotting cantaloupes and mildew.

The black cat leapt up silently, startling David, and teetered on the thin edge of the container, his hairs on end, sniffing. His whiskers twitched as he bared his teeth while analyzing the wealth of smells, and he jumped in and slinked to the face of the corpse and started licking the lips. This must be it, there’s whale cream in the lipstick, that’s like fish, and for the cat, irresistible. But this is a crazy cat, you can’t draw any conclusions from his behavior.

David put his thumb on the man’s lower-lip and swiped quickly, shivering, while the tomcat growled; it was cat food. The cat leaped at his hand and bit him. He withdrew the hand; it hurt but wasn’t bleeding. The tomcat continued licking the lips. David checked his thumb; it was greasy. What was the corpse doing in his yard? The city is not small. Is this a coincidence? Does this have anything to do with me? How could it? And how could it not? He brought the thumb to his nose, and it smelled like a fancy feminine smell, like Obsession. He had no idea what the damned Obsession smelled like, but maybe this was it. It should have an undercurrent of death to it, beneath the sensational effusion of purple lilies.

Well, I better get away from this dump, he thought.

He realized he didn’t have a sou on him, well of course, not a sou, but neither a kopek. Who bothered with kopeks anymore? Nor a ruble. He backtracked on Konyshnaya to Citibank on Nevsky, inserted his blue Citibank cash card, and withdrew 3000 rubles and three hundred dollars. What time warp was he in, he wondered, to still think of three hundred dollars? He would never pay that much for sex, forget it, it could not be worth it for all the anxiety attacks, pre-performance, post-performance. . . He looked around and hoped nobody was spying on him, no thugs, pickpockets, or other freelancers.

Luckily, he noticed two policemen standing on the curb. The police ought to be busy in this city. Should he tell them about the body dumped in his courtyard? They might find it strange that it was in his courtyard, plus didn’t he rub the epithelium cells of that man onto his fingers? Would the Russians be sophisticated enough to test him genetically? Maybe he should go right back to his apartment and clean his fingers. Oh, shit, didn’t he just pick his nose with the same thumb? Yes, it smelled like the damned lilies. He sneezed. What the hell, now it’s a bit late. The young man was clean, and the waitress who tried to resuscitate him, well, maybe she could have some kind of cold or whatever else you can transmit with your lips. The somewhat pharmaceutical smell of the lilies promised a disinfecting agent. It was probably all fine. If you started to worry about every touch and contact you have with human beings, there would be no end to washing and fumigating and scrubbing. And what would the waitress say? She put her mouth, exhaled, inhaled, salivated into the dead man’s mouth. Paramedics do it all the time. Why be such a squeamish gringo?

© 2014 Josip Novakovich

This story may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission.

Please see our conditions of use.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization

Josip Novakovich emigrated from Croatia at the age of twenty. He has published a novel, April Fool's Day (in ten languages), three story collections (Infidelities: Stories of War and Lust, Yolk, and Salvation and Other Disasters) and three collections of narrative essays as well as two books of practical criticism, including Fiction Writers Workshop. His work was anthologized in Best American Poetry, the Pushcart Prize collection and O. Henry Prize Stories. He has received the Whiting Writer's Award, a Guggenheim fellowship, the Ingram Merrill Award and an American Book Award, and in 2013 he was a Man Booker International Award finalist. Novakovich has been a writing fellow of the New York Public Library and has taught at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Die Freie Universitaet in Berlin, Penn State and now, Concordia University in Montreal.

Josip Novakovich emigrated from Croatia at the age of twenty. He has published a novel, April Fool's Day (in ten languages), three story collections (Infidelities: Stories of War and Lust, Yolk, and Salvation and Other Disasters) and three collections of narrative essays as well as two books of practical criticism, including Fiction Writers Workshop. His work was anthologized in Best American Poetry, the Pushcart Prize collection and O. Henry Prize Stories. He has received the Whiting Writer's Award, a Guggenheim fellowship, the Ingram Merrill Award and an American Book Award, and in 2013 he was a Man Booker International Award finalist. Novakovich has been a writing fellow of the New York Public Library and has taught at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Die Freie Universitaet in Berlin, Penn State and now, Concordia University in Montreal.