issue 41: March - April 2004 |

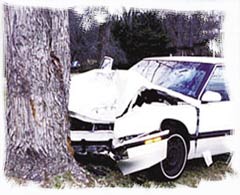

Humility HumilityPaul Bergstraesser You’re a rich bastard and you feel, for the most part, satisfied. You own a pair of Dobermans that patrols your estate in McAllen, Texas, six miles from the border of Mexico where your parents were born and lived and died in poverty. The Dobermans are kept lean on a diet of beef pumped with vitamins and water, plenty of water, and sometimes in the morning the dogs spoon together in a square of sunlight on the tile floor of the kitchen. But hold on, this story is not about dogs but about your wife, who is close to death and hasn’t told you yet. She has secretly been seeing a battery of specialists and they all give her less than a year to live; it’s not cancer but a degenerative disease in which the tiny air pockets in her lungs wither away, one by one, until she suffocates, which could happen while she’s swimming or gardening or buying a new handbag. While she’s been secretly seeing the doctors you’ve been secretly bedding a hospitalful of women, nurses through interns, sometimes patients, not bad for a forty-eight-year-old heart surgeon who has risen to the top ranks of his profession and flies monthly to Geneva. So why has your wife been concealing her impending death from you? Because a) she doesn’t want to worry you and b) she thinks you’re a bastard. She’s thought so since your wedding. Everything changed on that day. All the joy and love of a tender courtship were choked off when you leaned towards her in the church, in front of a crowd 500-strong, and said "You’re mine now." Later, at the outdoor reception, which included a Mayan pyramid built at half scale and a life-size donkey piñata filled with personal electronics, your wife found you holding hands with a caterer while feeding her deviled eggs. You explained that you were only being courteous to the help, that one shouldn’t forget the common workers, that they are the grease that keeps the wheels of society turning. Of course you never fail to mention the working class because you yourself were born of it. Here’s your story, every time: as a boy in Mexico City you stole Chiclets and sold them on the street, chewing up half your stash, your baby teeth rotting and falling out and then your permanent teeth also rotting yet somehow remaining precariously stuck in your head, constantly aching; the child of poor parents, who made thundering love to each other, trying to screw away their misery. When they died, one after the other, they left you enough money to give them a proper burial, but you decided on an improper one and used the balance of the cash for passage to the United States. Once there, you got a job as a hospital janitor in Brownsville, Texas, often breaking into the drug cabinet and gobbling down handfuls of Vicodin, less for the high and more to kill the tooth pain. At this point in your story you always pause for effect, take a deep breath, and reach into your back pocket, retrieving what appears to be a clear Ziploc weighted with small brown shells, but on closer inspection turns out to be a collection of decayed teeth. You smile broadly and say, "You want to know how I traded these for these?", holding the baggie next to your shining mouth, and you continue: night school for both your GED and bachelor’s, an inclination towards medicine, a kickass score on your MCAT, enrollment in med school at UT-Austin, a serious talent for heart surgery, residency at a top Houston hospital, a job offer at the same hospital, and then, and only then, a fully rehabbed mouth. There were women along the way, you say, a handful, small loves, but they were all ponds when your wife rushed in like an ocean, the most shockingly handsome woman you’d ever seen. By this time you were well established in your practice in McAllen; cardiologists faxed you from New York, Europe, India, inviting you to conferences, and if rebuffed, sought small bits of advice. Into this stepped your wife, an intern wanting to study with the best, her illness as yet unknown to her, or at most only the glimmer of death that all humans carry with them. Again, your tenderness drew her to you, and you ended up hiring, marrying, and firing her within a year. Nine years later you recline on the fifteen-foot couch in your split-level living room and watch your wife struggle to place a pitcher of lemonade and two glasses on the table in front of you. She falls back into a chair opposite the couch. Her shortness of breath half annoys and half concerns you - okay, three-quarters annoys - so you pop up and say, "I need to head back into work." "This late?" she asks. "I’m monitoring test results on Bill Seals. You know, I’ve talked about him before . . . the walls of his heart are thin as onionskin?" "Oh yes," your wife says. She walks you to the door and attempts to kiss your darting head, clicks the door shut behind you, collapses to all fours and crawls to the couch, sucking at all the air her deadened lungs can process, trying to take in a glass of lemonade that is immediately rejected. Outside, you chuckle lightly at Bill Seals, a name hastily made up several months ago when you first started in with this latest nurse, a bill of sale sitting on top of your desk as you called your wife with an excuse for not making it home that evening. You open the fifth garage door, the garage seven cars long; you love cars, driving not fixing. You choose the convertible Beemer and ride out into a May evening, your neighborhood lush and cool and canopied with oak trees, the adjoining neighborhood dry and hot, settling after a day of dusty poverty. The looks you receive there are never returned; you only notice the stoplights that impede your journey to the Doubletree Guest Suites where you book a room and phone Bill Seals and tell her to forget about panties and a bra, hell don’t even bother with pants and a shirt, just throw on a raincoat and get your dirty self down here. The next day you’re seeing patients, a noticeable bounce in your step, when you’re called to the phone between a potential bypass and an angina relapse, and your balls tingle and descend, thinking that Bill Seals is on the other end, but you clamp up at the labored mewing of your wife, who says, in a tiny voice, "she is dead. The lady. I can’t say—" And then you realize you’re wrong again; it’s not your wife but your housekeeper and she has called to inform you, in her own tiny voice, that your wife has passed away. The thought had crossed your mind before, her dying, but a lot of thoughts cross a lot of people’s minds and nothing means anything until your wife dies. The phone shakes out of your hand and the assistant catches it, hangs it up, and immediately marks off the rest of the day’s appointments with a large "X." Your eyes are chaotic as is the drive home, stoplights ignored, curbs soiled with vomit, the dashboard ripped clean of its moorings. When you arrive the EMTs seem to be taking a smoke break but hup to upon your distraught entry into the house. Your wife is on a gurney and clearly lifeless. You attempt to crawl onto the padding with her but, surprisingly, the smaller of the two EMTs pulls you down, tough love. She gives you a small speech and hug like she’s seen it all before. Actually it helps, although you spend the night fetal on the floor of three different rooms in the house, the final one the kitchen, where at dawn, their nightly surveillance complete, the Dobermans click in synch across the tile, stop, and lower their bodies around you. You leave nothing to chance over the next few months, nothing unexpected. Bill Seals shows up at the funeral and you send her packing with a glare and an unconscious twitch of the hand, severing her completely. Graveside, you tell your wife about the women and how you’ve gotten rid of them; you’re trying to "shore up" your life now, the practice is humming right along. You never attempt the word "sorry," not because you don’t feel it, but because you won’t be able to hold it together if you go that route. You treated your wife with carelessness and disdain; you ran your emotions through a prism of chaos and the threads of light were reckless and angry. One Tuesday evening, long after midnight, you back the Beemer out of the garage and flip open the hood. Lying heavy on the driveway is a bag of cement mix and you lift it part way, rip open the seal, and with a dusty thud drop it on the edge of the car engine next to the radiator. You fill the radiator with cement mix. You have been doing odd things lately and you accept them fully: not going in to work; watching the dogs grow fat on a diet of uncooked T-bones; rewriting your will to specify that upon your death you forgo the traditional manners of burial in favor of a funeral pyre. Your lawyer hemmed and hawed at this amendment but you upped his fee and he signed on the dotted. So you buckle in and drive out into the night, your fine German car expressing displeasure at the turn of events but nonetheless handling well as you tear-ass around your enclave (or so the zoning board calls it), driving up on curbs and grazing bushes, and as soon as you feel the front end get heavy you steer down into the adjoining ghetto (or so the zoning board calls it in private), and blow through a series of stoplights looking for the perfect tree, and when you find it you plow into it. The lights in the small adobe bungalow behind the tree flip on, neighborhood dogs bark, and by the time the homeowner has thrown on a pair of shorts and approaches, you’ve surfaced from your daze and stand wobbly next to the car. "You okay?" the guy asks. "Yes." The facial bruises haven’t purpled up yet. "You ruined my tree, cabrón. You drunk? Borracho?" "Keep it," you say. "The car. I’ll trade you the damage to the tree for the car. Some engine work, a new radiator, it’ll be fine." The guy pauses. "Help me push it into the garage." You assist and after an awkward handshake you limp back home, icing your face in the kitchen until the Dobermans waddle in and the sprinklers pop up for their dawn watering. The following Tuesday you outfit your Lexus with a radiator full of cement and the car seems unfazed by your addition to the engine; in fact the front end sparks along the midnight streets with hardly a puff of steam to warn of overheating. The scraping wakes up much of your chosen barrio and several people walk out onto their cement lawns to watch you tear around and when you finally connect with your chosen tree a small group gathers. The airbag keeps you conscious. The man who owns the tree approaches you with fear rather than anger, his three little children standing behind him while his wife peers from the doorway as though shading sun from her eyes. "My only payment for the damage is the car," you say, flipping the man your keys. He seems bewildered and holds them out at arm’s length. "Take them!" someone yells from the group. "But he’s loco," the man says. "So what, take them!" You hear all this from behind because you’ve begun your limp home, the airbag having cushioned most of the shock but your knee re-injured from the previous week. The two things you wonder most are where are the cops and why in God’s name are you doing this? The first answer is easier than the second: they’re busy patrolling your neighborhood and are too lazy or don’t care about this one; as to the second: it could be the jarful of depression pills you gobble down every morning, and it could also be . . . well, you’ll just leave it at the pills. If you look forward to anything now, it’s Tuesday nights - the blip on your lifeline. And, not surprisingly, so do the locals, many of whom have taken to stringing the palm trees in front of their houses with Christmas lights to attract your attention, others blaring music into their front yards so you’ll focus on their flora. They all line the streets as you charge by, stepping aside like a matador as you settle on your desired target. Cars three and four (another Lexus and a Land Rover) were pretty much the routine crash-and-give-away, the Land Rover recipient crying profusely and embracing your aching ribcage. You lost your front teeth, upper and lower, in the Jaguar collision, the steering wheel shattering under the force of your face, the people standing back in fear as you pulled yourself from the wreckage, ropes of blood swinging from your mouth as you laughed maniacally at the loss of your precious teeth. They thought you’d take time off after that one, but no, you were right there the next week, your vintage Cadillac crushed under a long palm tree whose heavy fronds thudded down around you. The first time your housekeeper comments on your change of habits is when the garage is down to one car. She, like your friends, has mentioned nothing about your general avoidance of others, chalking it up to grief, chalking up your injuries to rough debauched nights that every man needs after his wife dies. So one Tuesday morning she asks you why the lady’s car is the only one left. "I’ve given the others away," you say, and she continues mopping the kitchen, working around the dogs, who haven’t budged for several weeks. The ’84 Thunderbird was your wife’s favorite and it seems a shame to cut the seatbelts out, but you do just that, prepping it for the evening’s journey, thinking about how she clung to the car as the last remnant of her old life. You wash it and let it idle in the driveway; it coughs and sputters a bit, not unlike your wife, and when night comes you heave up a fresh bag of cement mix which tears on the hood latch, the thick dust pouring out of its stomach. You fill the radiator by hand, scooping up the dust, filtering it into the still hot opening. The engine revs angrily as you push on the accelerator. You slam the door shut and the car becomes enraged, a high scream piercing the night, alerting your fans of your approach. Your first pass is greeted with noisemakers, cheering, a regular fiesta; your second pass yields silence: an ’84 Thunderbird? I got one in the garage. That’s it this week, loco? Your third pass, however, quiets the skeptics because of your speed and the fury of the engine. Many are fearful and go back inside, most stand in awe as you target the unmovable oak at the end of the street. It stands alone in a small park and has been awakened by the commotion, its branches rustling in irritation. Your personal silence comes before that of the car. You’re conscious as you burst through the windshield, the sound of the crash still expanding as the oak mashes your shoulder down to your waist. Convinced the Thunderbird can’t be salvaged, one of your fans takes pity and calls the cops. They arrive; door-to-door questioning is met with blank stares, the car is towed, your body zipped up and transported to the morgue by a couple of EMTs who still feel no compunction about smoking around fresh corpses. Your backyard burial is attended by your lawyer, housekeeper, and two dogs. Your polite friends consider a funeral pyre barbaric and refuse to come. The assembly of a pyre is no easy task; the lawyer hires two shady woodcutters who erect a solid, readily ignited structure. They place your body in a cradle of soft wood that is designed to fall into the center of the flame at its height. As the flames begin to lick up around your hardened flesh, several cars show up at the front gate, honking for entrance, and the housekeeper lets in a Land Rover and two Lexuses packed with people, children and adults, who form a solemn circle around the fire. At this point, if I were a storyteller, I’d say that the ashes were lifted by the heat into the southern sky, riding the whips of flame, drawn to the hot Mexican sun that knows humility more than it knows excess. But I’m not, so I’ll just say that, as the pyre dies down, the people load back into the cars and drive away, and later that week your lawyer employs an extra landscaping crew to pretty up the yard. |

| © Paul

Bergstraesser 2004 This story may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission. Please see our conditions of use. |

author bio  Paul Bergstraesser has won several prizes for his writing, including an Illinois Arts Council Literary Award. He is currently pursuing a PhD in English/Writing at the University of Illinois-Chicago and writing a novel on Dada and baseball. |

navigation: |

issue 41: March - April 2004 |

||||||

|

|||||||

Home | Submission info | Spanish | Catalan | French | Audio | e-m@il www.Barcelonareview.com |

|||||||