RICHARD SCHWEID

RICHARD SCHWEID

CONDI RICE’S FINGERS

The waiting room where I sat while my younger brother had his prostate biopsied was full of old guys like us. I marveled at their calm. They sat quietly, hands folded in their laps, or thumbing through magazines, or looking at the screens of their cell phones, and a couple of them were talking softly to their accompanying wives. Even in the most optimistic of scenarios, none of us had long left to stay on the planet, we were right up against it.

How could we keep on with our quotidian lives, I wondered, all of us looking right down the barrel of the gun? Yet, here we sat, carrying on as if we had all the time in the world. Everyone in that waiting room, including myself, was already pretty far along, each of us trailig a string of parents, family, friends, all of whom had gone on before. I found it valiant that they—we—could all sit so quietly, so orderly and behaved, no shouting or terrified, desperate protesting, as our existences drew to a close.

And even here, for god’s sake, prostate problems or not, when the nurse in her tight, white uniform walked into the waiting room through a green, swinging door to call another unfortunate back to the torture chamber, all of us old roosters watched her, noted the swell of her breasts, undressed her in a quick flicker of imagination, all of us still under the pull of the biological imperative even with one foot in the grave, and our prostates delivering us to abject humiliation. Some of the men in that waiting room were wearing coats and ties, and others were wearing jeans, but in the prostate biopsy chair they would all be naked from the waist down, feet up in the stirrups, helpless, legs latched apart, sheet draped across their kneecaps, and the doc would come at them with a needle longer than their middle fingers.

My morbid thoughts were interrupted by a sudden racket back in the direction of the examining rooms, a crash and the sound of a lot of glass breaking at once, as if a cabinet full of glassware had fallen to the floor. That noise was followed by my brother’s raised voice, which I could hear plainly all the way down the hall. “Goddammit, I told you, do that one more time and I’m gonna…”

The nurse was right behind him as he spilled out into the waiting room, walking kind of funny as he came through the swinging door in his sock feet, shoes dangling in one hand, legs bowed out as if he was holding a ball between his thighs, something about the size of a soccer ball. He was stepping gingerly, red-faced, buckling his belt. He lowered himself carefully into the empty chair beside me without acknowledging my presence, and bent over, wincing, to put on his shoes. The bald spot on the crown of his head was as familiar to me as my own face. I lifted my palms toward the nurse and smiled apologetically, hoping to communicate that everything was under control.

It was so quiet in that waiting room it was as if all those old folks had up and died at once. Then, what you could hear was the nurse on a phone, telling someone to send security to the doctor’s office, and I didn’t wait for my brother to finish tying his shoes before yanking him to his feet and pulling him toward the front door. He acquiesced, grasping the need to skedaddle. With my hand under his elbow he kind of lumbered along beside me as if he’d crapped in his drawers, and about every step he was muttering, “Ow, ow, I shoulda killed the son of a bitch.”

I got him tucked in the passenger’s seat, and got us out of there. ”Oh man, you have no idea,” he told me. “I thought they were gonna stick me once, and that would be that. Guy must have hit me with that long needle about twenty times. Enough is e-fucking-nuff, I told him, you’re gonna find cancer or you’re not, don’t do that again or I won’t be responsible, but he just kept jabbing me, and saying, ‘We’re almost done, we’re almost done.’”

My brother’s prostate biopsy turned out not to matter because within a year brain cancer, a glioblastoma, had bloomed in his head and eaten him up. It wasn’t long after his diagnosis that he decided we were going to break Condoleeza Rice’s fingers. She had been Secretary of State under George W. Bush, and one of the chief architects of the Iraq war. The same war in which my 22-year-old nephew, the oldest of my brother’s two boys was killed, burned to death inside a molten mass of what was an armored vehicle before a rocket-propelled grenade lit it up.

My brother had served in Vietnam. When he got back from the war, and married my sister-in-law Amanda, he was a seriously spooked person, and was determined to settle down for life. He’d tried his damndest to convince my nephew not to enlist. When my brother got back, he went to school on the G.I. Bill and became a pharmacist, working for the main street pharmacy in our small Tennessee city, and eventually buying out the owner when the old man finally retired. Ask my brother what he liked to do for fun and he’d tell you right out: “Spend time with Amanda and the boys.” He was always glad to surround himself with family life. I’ve never seen another father enjoy his kids like my brother did.

Once he saw he could not dissuade his firstborn from joining, my brother told me that he and Amanda hoped the boy would get his fill of adventure in Iraq, and come back to settle down. To peacefully occupy his own place in the world. It was when those two Army bearers of bad news showed up in dress uniforms, ringing the bell at his door, that my brother really began to die, five years before the doctor diagnosed the stage-four glioblastoma.

After a seven-hour operation taking out as much tumor from the brain as he dared, an august and authoritarian surgeon called us into his office, and that’s when we learned that horrible and vomitous noun: glioblastoma. The surgeon didn’t mince the words he spoke in his German accent. Survival was plotted on a Bell curve, he explained: some die within months of being diagnosed, others live longer than a decade, but the great majority make it to about a year and a half.

It wasn’t too long after his surgery when my brother started to slow down, and go quiet. He stopped going into the pharmacy, leaving its daily management to an assistant. My sister-in-law Amanda took an extended leave of absence from her job as a secretary at City Hall to care for him. Evenings, I came over to his house after supper, and we watched TV together. It was baseball season, and we watched the Houston Astros every night. He sat in a deep, easy chair with a pillow behind him, and I sat on the couch with the remote control. Amanda had her own easy chair, next to my brother’s, and she generally read while we watched the game, or took advantage of my presence to do her own tasks, which she did not have time for while she was caregiving all day. I muted the ads between innings, although none of us had much to say.

If the weather hadn’t been thunder and lightning in Houston that night, the whole thing might not have come up, but the game was rained out. Surfing the channels for something else we lit on the local public television channel, which was showing an Oscar-winning documentary called The Fog of War. It was about Robert McNamara, ex-Secretary of Defense. The war in Vietnam is often referred to as McNamara’s war, because of how avidly he promoted and pursued it during the presidencies of John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. The film consisted of archival material, plus interviews with an elderly McNamara in 2003, six years before he died in his sleep at the age of ninety-three. A carefully groomed McNamara, grown old, who exhibited a slight contrition for his tactical errors during the interviews, but never acknowledged the blood, injury, mayhem, and death that he had caused so many human beings, much less apologized for having done so.

My brother watched without a word, and when it was over he said goodnight immediately, and went to his bedroom. I wasn’t sure how much attention he’d paid to it, or whether it had registered at all. In those days I wasn’t sure where he went in his long silences. I could no longer guess what, if anything, was on his mind. He never spoke of his glioblastoma; he had obviously decided not to bring it up, and both Amanda and I respected that.

The next night, Amanda was out to a book club meeting at the library, and we were watching a lopsided game in which the Astros were down by six runs. He suddenly began speaking, anger filling his voice, and said more than he’d said in weeks.

“I couldn’t believe it, man, I never thought I’d live to see the day when that bilious sack of lying shit McNamara, forty years down the road, would sit there in his rich living room, him old as the hills, and healthy, and comfortable. So many dead I saw, he wiped people out like you’d erase pencil marks, here one minute, gone the next, young guys with their whole lives in front of them, dead for nothing at all. That slimeball never paid anything. He should have been executed. Instead, there he is, eighty-seven, and still being fawned over, treated with respect,” my brother was nearly shouting. “He slaughtered people, brother. Slaughtered people by the thousands in Vietnam, and never paid anything for it.

“Listen, while I’m still able to do it I want to extract a price from Condoleezza Rice for the stupid war in Iraq. I don’t want to leave her to enjoy the rest of her life like my boy can’t, and come on TV in forty years having lived out her whole life after pushing the Iraq war. She’s an accomplished pianist, playing the piano is a big deal in her life. We’ll break her fingers. Every time she thinks about playing, or even hears music, she’ll remember how her fingers don’t work so well anymore, and then she’ll remember why, and think of those mothers and children whose lives she tore apart with her haughty, horrible ideas.”

“Whoa, bro, who’s that we you’re talking about?” I asked.

“I’ve got it all thought out. She’s teaching international policy at Stanford University out in California You email her that we’re journalists doing a piece, and get us an appointment with her. Or, tell her secretary we’re historians doing a book on secretaries of state, and we want to interview and photograph her. You know how to do that kind of stuff. Ask for fifteen minutes. I’ll have a loaded plastic syringe taped under my arm. I know just what to use. When we get in to see her, you get her to hold still for a photo, just long enough for me to jab her. She’ll be down in a jiffy. What’s more, it’s merciful, when we do her fingers she won’t feel anything. Of course, when she wakes up it’ll hurt quite a bit. Like, for the rest of her life,” he smiled tightly. “We’ll break her fingers, leave her there on the rug, close the door on the way out, and nod goodbye to her secretary.”

He passed me his laptop. There she was: dark skin and white woman’s hair-do, long, graceful fingers, a small smile that didn’t reach her icy eyes; she was tall, erect, prim and proper, an altogether exemplary person, but some admirable human quality was missing, a vacuity in her gaze, a lid clamped so tight on her feelings that she could slaughter mothers and children in the service of an abstraction.

“For her, collateral, civilian deaths did not happen to people who liked to play—or listen to—a piano,” my brother said. “Perhaps one of the children killed by one of the bombs she sent would have grown up to be a great piano player. This thought does not occur to her, brother. She served war, not peace.

“You know she goes through every day without a sorrowful thought for all those people she helped kill, families whose lives she ended or maimed. You see her? Look at her. She’s in good shape. She has decades left to enjoy being alive. I don’t think that’s right, and I think it’s up to us to do something about it.”

It was the most animated I’d seen him since his diagnosis. I was glad to see it, anger is a sign of life, and my brother was born with a temper on him, which had only increased over the years. Anger at politicians was one of the keys in which his life came to be played. Maybe it gave him a certain strength, or maybe it birthed a tumor. I don’t know, but it was a part of the way he was in the world after he got back from Vietnam, and I was glad to see it still flashing. Nevertheless, I had to remind him that falling afoul of the law, and going to prison, was something to avoid at all costs. It would be like the Army, but much worse, I stressed.

“Not a problem,” he said. “We won’t get caught. Keep our fingers off the furniture, we just have to be careful not to leave any prints, or DNA around. None at all. Once she’s down, we put on gloves. It’ll be quick work. See those skinny fingers? I won’t have any trouble breaking them at the second joint, and we’ll be out of there. No reason in the world to connect a couple of guys from Podunk, Tennessee to it.”

We decided we’d fly to San Francisco and rent a car, drive to Berkeley, break her fingers, and be back at the airport that night in time to catch a red-eye flight back to Tennessee. For a while, we spent evenings carefully plotting our movements, planning exactly how we would do it, the flights we would take, the routes we would drive in a rental car, the clothes we would wear, the camera we’d carry. One day he managed to drive himself to the pharmacy, and that night a plastic syringe full of liquid appeared in a small zip-lock bag at the back of one of his refrigerator’s shelves. He showed it to me with pride. “I told Amanda it was de-worming medicine for the dog. It’ll knock down a horse. Condi won’t know what hit her.”

Night after night we planned, checked distances, flight times. Mostly what we did was imagine how shocked Condoleeza Rice would be when she woke up howling on her office carpet with her fingers broken. I’m kind of sorry now we spent so much time thinking about such an ugly scene instead of something more meaningful, but that scenario is what he wanted to contemplate. We spent a long time considering what to say in the note we would leave beside her on the carpet, which would be made from letters cut out of a New York Times, and pasted on a sheet of paper to form our missive. We finally decided to keep it short: “For the mothers and children of Iraq” it would say. We hoped she would read it, and instantly understand why she was being punished.

It wasn’t long before it became clear that it wasn’t going to happen, although we didn’t talk about that, either. My brother stopped being able to walk, or get to the bathroom without help. His last couple of months were spent in a hospital bed by the picture window in his dining room. The bed was brought by a hospice service, as were the nurses who came morning and evening to tend his body, its bags and catheters. I was in his house most evenings. He’d lost interest in the television, and mostly slept. I passed the time playing backgammon with my 18-year-old nephew, my brother’s youngest, who was home on emergency leave from his first year studying pharmacology at the state university.

We played at the dining room table, while my brother lay pretty much silent on the hospice bed, and the tumor in his brain marched his body inexorably toward annihilation. Sometimes, just so I could remember what it felt like to feel good, I sampled the pain medications among the pill bottles laid out on the nightstand next to his bed.

My nephew, the aspiring pharmacist, caught me at it one evening, pill bottle tilted over my open palm as I tapped on it, and waited to catch a bit of relief. “Whoa,” he said, “you don’t want to mess with that stuff, Uncle Bob. It’s strong.”

I nodded assent, threw my head back, and swallowed dry the little yellow tablet.

* The pills that were left over after my brother died are long gone, and I can’t remember the last time I felt good. Now, here I am, two years later in a different waiting room, among a different group of old guys. I’m about to have my own damned biopsy. The urologist says my “high PSA numbers” make it likely I have “some” cancer, and if so he’ll cut out my prostate like a brown spot on an apple. It will need to be done, he tells me, if I don’t want the cancer to spread to my bones. And, I don’t. Cancer is not how I would choose to go. I watched my brother, and came to believe I’d prefer a lightning bolt, or a sudden decline of a few days, a quick fade and some hurried goodbyes. The slow dissolve is something I’d like to avoid.

My brother’s gone, and here I am. Back in a waiting room. Waiting.

Let this serve as a warning: Watch out, Condi. Watch out.

© Richard Schweid 2025

This story may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission.

Please see our conditions of use.

Author Bio

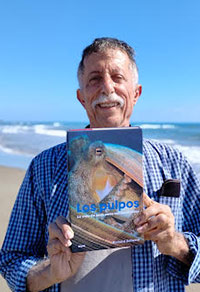

Richard Schweid is a journalist and documentarian from Nashville, who has lived in Barcelona for decades. He has a dozen books of nonfiction published about a wide variety of subjects listed at www.richardschweid.com

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization