issue 51: January - February 2006 |

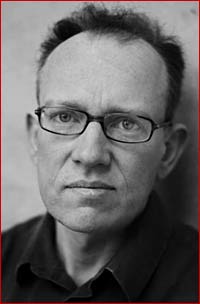

Interview with Interview with James Meek by David Ramos Fernandes Having just returned to London after a trip around North America promoting his latest novel, The People’s Act of Love, James Meek kindly agreed to meet for an interview. Since it was first published in July 2005, the novel has received overwhelming praise and recognition, including a Man Booker Longlist and Saltire Book Of The Year nomination. He has also been awarded various prizes for his journalism, including the annual Pris-Bayeux-Calvados for War Correspondents and the Amnesty International Award in 2004, leading him to be described as ‘one of the finest foreign correspondents of his generation’. Born in London in 1962, Meek grew up in Dundee, Scotland. He has published two previous novels, Mcfarlane Boils The Sea and Drivetime, and two collections of short stories, Last Orders and The Museum Of Doubt, as well as contributing to the acclaimed Rebel Inc anthologies The Children Of Albion Rovers and The Rovers Return. Meek began his newspaper reporting in 1985. He lived in the former Soviet Union from 1991 to 1999. He now lives in London, where he writes for the Guardian, and contributes to the London Review of Books and Granta. TBR: In an article for the Observer, you stated that your experiences as a journalist and correspondent have little influence on your fiction. What then was the main inspiration for the novel? JM: I’m not a journalist all the time remember. I mean, when does being a journalist stop and being a human being start? If an accountant was sent by their firm to Nigeria for a couple of years, and then that accountant wrote a novel about Nigeria, would that novel be based on their experiences as an accountant or their experiences living in Nigeria? People usually phrase the question in a different way, about different kinds of writing, which is a fair enough question. I’m just getting bored with it. When I finished my previous book, Drivetime, and I was thinking about writing another one, I hadn’t planned to write a book set in Russia. I actually had the beginnings of an idea set in Scotland. Most of my books have been. It’s kind of odd really, because I had already been living in this extraordinarily eventful environment, having this rich life of experiences, in the Ukraine first, and then Russia. I had already been there four years, and I’d seen a lot of remarkable things, been to remarkable places and spoken to remarkable people. And yet I’d utterly rejected the idea of writing about Russia; there was something in me that was prejudiced against it. I didn’t quite know why. Perhaps it was because I was a journalist, I was afraid of allowing the two things to get too close. Also, I think it was influenced by the awareness that almost all my journalistic colleagues were writing or had written books, and I felt there was going to be this great flow of books about Russia, by somebody who thought ‘I’ve been to this remarkable place, I’ve done these remarkable things, I must be able to write about it.’ I felt that wasn’t sufficient cause. At about the same time I heard about these situations, and I call them situations rather than stories, because the stories are mine, they’re my invention, but the situations are real: the idea of premeditated cannibalism by prisoners escaping from Arctic prison camps; the existence of this Czechoslovakian legion in Siberia after the civil war; and the existence of this cult of castrates. People talk about research, but very little research has gone into this book. It’s true that before the book was finished I read at least one book about each of these situations—pretty much what’s acknowledged in the back—but the essential idea of those three situations is not research-based. They’re ideas that someone could pitch—the sort of thing you could pitch in one sentence. And it was those very simple, but very extreme situations which stimulated the immediate appearance of characters in conflict. And I thought I could just use one of these situations, because any one of them could have made a book in itself, but I thought, they can only really be set in Siberia in 1919, and I’m only ever going to write one book set in Siberia, so if I don’t put them all in then I’ll lose one of them, and that would be a shame. I thought it would be very difficult, very ambitious, that it might not work, but I was going to try. It turned out that it was very difficult. At one stage I became discouraged, and instead I went and wrote The Museum of Doubt because I had a firm proposal from publishers, whereas the very early response to the first few chapters of The People’s Act of Love was lukewarm. I didn’t have an agent at the time, so what I was showing agents didn’t go down very well. When I got back from Russia, having finished The Museum of Doubt, I got an agent and she was quite encouraging about the book, so I decided to go ahead and finish it, and the rest is history. TBR: There are numerous instances within the novel that jar with our expectations of time and setting. Most obvious is the contemporary prose style, but there were other, more physical instances, such as Matula taking cocaine or Anna’s explicit sexual desires. What was your intention in doing this? JM: Well, people have always been having sex. But I mean—that’s not something that anyone else has really mentioned—I suppose it takes a writer to be interested in these points. I didn’t see it that way when I was writing it. In a sense, everything is deliberate of course. I never expected to find myself writing a novel set in the past, though it is certainly on the threshold of modernity. I just wonder what you think the alternative could have been? TBR: Perhaps something more along the lines of the period’s style and convention, or even what we recognise as a more conventional, historical novel? JM: The last thing I wanted to do was the conventional, historical novel. I would challenge your phrase about the period’s style and convention too, because that was a time of extraordinary diversity and creativity in Russian letters. You’ve got people going off on all sorts of directions. Andrei Bely—I don’t know if you’ve ever read Petersburg, but it’s an extraordinary book. It’s not an easy read, but it’s got this fantastic richness. I’ve got to the situation now where I’m poised between reading Russian well enough to feel that I have to read books in Russian, but not quite well enough that I can do it without a dictionary at least in the next room. But I couldn’t do that with Andrei Bely because his writing is so rich. It’s really deep, luscious prose. But then that’s completely different from Bulgakov, who was working in a Chekovian tradition before starting to make something of his own. And then Platonov, who was a unique stylist. And scores more who I’ve probably never even heard of. I don’t think there was one style. And I think that there are—and I hesitate to use the word modernity here but—there are styles in early twentieth century by masters and mistresses in early twentieth-century Russian writing who most people writing in English are not even aware of, and have yet to catch up with. It may be that twenty years down the road everyone will be adopting the style of Bely or Bulgakov or Platonov, and this will come to be understood as modern. But then, that doesn’t really answer your question. TBR: So there wasn’t a deliberate attempt to emulate any one of those writers? JM: No, there wasn’t an attempt to emulate those writers. It’s not a book which has been written as if it’s been told by a contemporary narrator. The narrator is invisible. Occasionally there is some kind of apostrophe on my part, but that’s as far as it gets. Of course there are considerable sections of the book which are told specifically in someone else’s voice, and I think that the style of Balashov’s letter is rather different. I think that style is dictated as much by how you deal with your organisation of time and space, and the proportion of dialogue to reported speech, as by what you do on a paragraph by paragraph basis. Um. I’m not being very clear here am I? TBR: It has been remarked that its subject matter and style are very different from your previous novels and short-story collections. What provoked this change, and was it a change you really wanted to make? JM: No. Certainly not. But in the course of this very long process of writing, and indeed stopping writing and then writing something else, and then writing this again, you’re bound to change over ten years of your writing. I feel I have changed, I have had new thoughts. I think that in certain parts of The Museum of Doubt, in the Gordon stories, at one point, Gordon and Charlie go to this teashop and meet these two women. At the time, for me, I spent an unusually long time writing that whole sequence: four people in a single place, like a play in a way. I think that was the moment. I thought, why am I doing this, why is it taking me so long to write this. Why is it taking me a day thinking about a sentence? And then I read over what I had done, and I thought, right, now I understand why it took me so long. Because it works. And so my question was not, why am I taking so long over these two or three pages? But why did I not take as long over all the other fucking pages I’ve written. It’s not exactly carelessness, because I’m not someone who would write a page of fiction, make a few hasty corrections and then move on. Everything I’ve ever had published, and not all of it I’m happy with now—because I have been published for a long time now; I started quite young—but even the stuff that now I’m not happy with, I can still see that I’ve read through each sentence many, many times and I’ve tried to make it okay, make it fit; but there’s a degree of care and thought in the composition that I don’t think I’ve applied until recently. A degree of studying the characters in your imagination, looking them in the eye, accepting the full truth of what they are and what they want and will do. It sounds obvious, but in the past I’ve not always done that with the characters, creating an outline for them and perhaps a set of behavioural characteristics. In my mind they’ve been quite fully formed, but that hasn’t necessarily come out on the page. Although, saying that, I look back on the characters in Drivetime and I think they are quite well-portrayed. It’s not so much that I’m not taking care of my characters, but I think I was taking short-cuts in using various devices and tricks to make my life easier. Instead of staying with a character and really focusing on them, I was perhaps just starting off in some other direction, making the narrative more episodic and more funky than it should have been. TBR: Would you say that your intentions have changed, as opposed to your approach? JM: No. I would say it was my approach that has changed. It’s interesting about Gordon because when that book was published, me and Kevin Williamson, my editor on that, we had a discussion about it. It’s a book of fourteen stories, and in amongst the stories there is a sequential narrative, and we said, well, should we put them all together in one, as a novella, or should we scatter them through the book? At the time we decided to scatter them, but I now think that was a mistake. When the book is re-published next year I’ve decided to place the short stories first, then the novella. I’m going to have to read over all of it again and verify that what I say now is true, but what actually happened during the course of writing The Museum of Doubt was that my style changed. It seems to me that in those six stories you can see the whole Meek line. It starts out as I started out, and it ends up as I’ve ended up now.

JM: I think that’s true of Matula, but I don’t think that’s true of Gordon. I think Gordon is very troubled and unhappy. His frame of reference is out of whack. But Matula is definitely somebody who is immune to other people’s feelings, like a sociopath, but what interests me more, on a fundamental level—and this is something I am going into more deeply in my next novel, the book I’m writing now—is just the impossibility of knowing someone else; the lack of intimacy even in intimacy, let alone the lack of intimacy at any other time; the failure of sympathy between individuals and between countries. Kundera talked about the unbearable lightness of being, and it’s a great book, but there’s also the unbearable solitariness of being. In reference to Gordon and Matula, I suppose, yes, perhaps that is an over-arching obsession of mine. TBR: Is there any particular reason for that obsession? JM: Probably. TBR: In one your articles for the London Review of Books, you wrote that ‘the advantage of a story set in wartime is that all the characters are obliged to form a relationship with death’. In reference to The People’s Act of Love, do you believe that war then becomes a form of romance? JM: Yes. Definitely, that’s why they’re so popular. It’s what makes beauty so attractive: its transience. We never desire anything so much as when it is about to be taken away from us. That’s the thrill war always provides. TBR: Anna Petrovna was a very different, but no less striking, character to the others in your novel. For one, she is the only main female protagonist of the story, but this difference was enlarged by an almost empty sensuousness she possessed. She was pragmatic, but also desperate and needful in her desires and craving for, among other things, sex. What brought about her story? JM: She is different from the other characters, but I think she’s more well-adjusted, more normal than the other characters, if you can talk about normality. Normality is not a very good word to use. She’s the one who’s the most ready to flourish and prosper in a peaceful environment. A few other people, often men, have made that remark about Anna’s craving for sex. I think that’s a bit harsh. If it was a man I don’t think there would be anything surprising about it. Women do feel the same craving that men do for sex. I’m only writing what’s true. It’s interesting that it still seems surprising. I mean, remember the situation that she’s been in. Her husband has cut his balls off. It’s quite a harsh rejection. I don’t know what your experience of women has been. You’re still quite young obviously, but believe me, women do feel the same craving. Not all women, but many women. I don’t really feel I’ve laid it on too thick. It’s not like she’ll just jump into bed with anyone. TBR: One of the scenes that struck me is when she pays a neighbourhood boy to masturbate her. It is raw and explicit in much the same way as the sudden acts of violence that punctuate the novel, such as Matula dashing the sable’s head against the table. The descriptions are explicit and provocative. JM: The thing about Anna is that she is the axis around which the book turns. She’s also a character that faces both ways. Mutz is a sensible, clever, thoughtful, self-aware man, but he lacks the passion and the fire, the hunger, the extremity of longing that Balashov and Samarin have. They have that, but they lack Mutz’s sense of proportion and caution, delicacy and restraint. Anna understands that it’s much better to be like Mutz, but she also can’t deny the part of her that yearns for people like Samarin and Balashov, even though they end up treating her very badly. So, in that sense, she’s a fuller human being, but that doesn’t mean she’s happy, because she’s flawed. Whichever way she moves, she knows it can be very difficult to find that balance. But that’s the situation that we’re all in, assuming you and I are normal, whatever that means. I can’t believe how often I use the word normal. TBR: You might not like this question, but if any other writer could have written your novel, who would you choose and why? JM: Um. Cormac McCarthy. But that’s quite a strange question to ask. TBR: At the beginning of the interview we briefly touched upon your experiences as journalist. In a recent interview you said that you wanted to ‘watch your characters closely, study them, and not to flinch from what it is that you know they must do’. This sounds very much like a war correspondent’s approach to fiction. JM: Well, in that sense, if you like, there is a comparison. The difference is that the person you’re not flinching away from, in fiction, is yourself. Not somebody else. That’s what makes it different. To tell the truth about what you believe human beings are like is very difficult, as is telling the truth about yourself, because that’s the only real laboratory you have with which to examine humanity. It all comes down to this question of truth and sincerity, because whatever a writer puts in their books about what people do, it’s one of two things: it’s either something that they can, on some remote level, believe themselves to be capable of doing; or it’s just a fake vanity. That may seem to be a very harsh and radical statement, but I think it’s true. It’s not like I’m on the verge of castrating myself, or that I think it’d be a really sound idea if, instead of taking a packed lunch with me next time I go climbing, I took a friend to eat once we reached the top. That’s where your imagination comes in. You have to take the cadences that you see inherent in humanity, and in yourself, and extrapolate them to different life-histories, different cultural contexts, eras, situations, and think what you might do. I had this very uncomfortable moment last time I was in Iraq in July last year [2004]. When you’re driving around the threat is always there, that somebody was going to stop your car and kidnap you and cut your head off, but I’d already written the bit in the book where Mutz is faced with his own execution. It felt very curious. It’s one thing to write about, and of course, when I wrote it I had already been to Iraq, I’d driven around thinking I’m going to be kidnapped; but then I had written it, and now I was back in Iraq thinking I might get kidnapped and executed. That’s a real test for your imagination. Of course, the greatest test would have been if I had got kidnapped and got my head cut off, but fortunately I wasn’t ever put to that test; but even to get to the point where you’re imagining not how somebody would react in this circumstance, but how you would react—which could come at half past two that afternoon—it helps focus your mind on how rigorous you have to be with your imagination. TBR: There was a particularly illuminating passage in the novel which correlates to your profession as a journalist: ‘I hated the way everyone lied; the lawyers lied as their profession; the bureaucrats about how honest they were, the priests lied about being good, the doctors lied about being able to heal the sick, the journalists lied about all the liars’. How acute is that sentence with your own particular view? JM: You spotted that. Well. Yes, I’m being harsh on myself. But in part, I know that’s how people think about journalists, so, you have to be realistic about the professions which historically, and to this day, people hold in casual contempt. So, on that level, it doesn’t necessarily mean that I agree with it. I’m just trying to be true to what people think and say. There are lots of ways of lying of course. TBR: In a recent article you wrote on Iran, JM: He was kind of crazy remember, but yes, I definitely have responsibilities. You use the word choice. That’s the critical thing in journalism. Journalists don’t lie as much as the public or the readers think they do. Some journalists lie more than others. I’ve never made anything up, but I know reporters who have. I know reporters who’ve made up stories, made up people, made up places, but it happens much less than the public think. I’m just talking about lying. Then you get into more questionable realms of describing things in an inaccurate way; if something happens, or you meet somebody and the person is genuine, and the thing really happened, but it just didn’t happen the way you said it did, that’s the next layer. Then you get into the whole business of choosing what to say and what not to say. Not a lie, but sometimes the choice is so fiddly, and the space is so limited, that it can almost seem like a lie.

Well, in journalism it’s usually some other constraint, the constraints of space and time. And also, it must be said, the limits of the readers. TBR: Is that a concern? JM: It is for the editor. They have to sell papers. TBR: Isn’t that a problem? You’re thinking what the editor’s thinking, the editor’s thinking what the reader’s thinking? JM: There’s a lot of second-guessing going on. But that’s all journalism. Those constraints don’t really apply to the writing of fiction. I think, after what I’ve said, you should be able to understand why I’m making the point that, different as they are, it’s actually harder to be truthful in fiction than it is to be honest in journalism. TBR: I was expecting you to say the opposite. JM: It’s much harder. TBR: Why is that? JM: Because it’s harder to tell the truth about yourself, and what you think about other people, than it is to simply report what happens and what people say to you in the safe guise of a journalist writing about a specific series of actual events. There’s always a place that journalists can’t go, and that’s where the imagination comes in. You have to fill in the gaps. TBR: I read in another of your interviews that you thought ‘the observation is the writer’s; the judgement is the reader’s’. I thought this was quite an accurate statement to make. Do you still feel this way? JM: Yes. I mean, it’s an ideal, but it’s one

that’s not always worth realising. Sometimes I do like it when a writer makes a

judgement. Sometimes it works. There are passages in a The People’s Act of Love

where I do make some statement about the way things are, and I think there are going to be

more of them in the next book, but the next book is told in a different narrative style. I

think it’ll be seen as being the judgements of the main character rather than my own.

s See TBR's review of The People’s Act of Love by James Meek |

| © TBR 2006 © author photo: Cannongate This interview may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission. Please see our conditions of use. |

| navigation: | issue 51: January - February 2006 |

fictionComing of Age David Ramos Fernandes: Storage Nora Pierce: Guess Who Loves Me Now? Caroline Kepnes: Companions Katie Arnsteen: Long Ride Home picks from back issues Fun With Mammals Adam Johnson: Trauma Plate interview quiz book reviews

|

Home | Submission info | Spanish | Catalan | French | Audio | e-m@il www.Barcelonareview.com |